Medication adherence—defined as taking medication as prescribed—is a crucial part of aging well. However, 50% or more of U.S. adults do not take their prescriptions as directed, and medication nonadherence is responsible for as many as 33%-69% of hospital admissions and 125,000 deaths annually. The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the importance of medication adherence, stating that, “Increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatment.” There are many factors that contribute to non-adherence, such as financial barriers in purchasing medications, lack of access to healthcare, and lack of physician-patient trust.

Although more medications are taken at home than in hospitals and clinics combined, the impact of home medication management on medication adherence is understudied. In addition, medication adherence concern is greatest for older adults since 67% of U.S. adults 45-64 take at least one prescription drug, rising to 88.5% for those 65 and older. Older adults may also view health in general and medication adherence in particular as an important component of aging in place. For these reasons, we chose to focus on effective home medication management strategies and habit formation in relation to adherence among older adults.

Medication adherence—defined as taking medication as prescribed—is a crucial part of aging well. However, 50% or more of U.S. adults do not take their prescriptions as directed, and medication nonadherence is responsible for as many as 33%-69% of hospital admissions and 125,000 deaths annually. The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the importance of medication adherence, stating that, “Increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatment.” There are many factors that contribute to non-adherence, such as financial barriers in purchasing medications, lack of access to healthcare, and lack of physician-patient trust.

Although more medications are taken at home than in hospitals and clinics combined, the impact of home medication management on medication adherence is understudied. In addition, medication adherence concern is greatest for older adults since 67% of U.S. adults 45-64 take at least one prescription drug, rising to 88.5% for those 65 and older. Older adults may also view health in general and medication adherence in particular as an important component of aging in place. For these reasons, we chose to focus on effective home medication management strategies and habit formation in relation to adherence among older adults.

After conducting a survey study on home medication practices, we wanted to conduct an interview study to talk to older adults directly about how they manage their medication in their homes.

Semi-structured qualitative interviews using an interview guide were conducted with 22 participants on Zoom during August 2022. Each interview took around 45 minutes. Consent to participate was obtained at recruitment, and consent to record the interview was obtained at the start of the interview. Thematic analysis was performed by reviewing and coding interview recordings and transcripts.

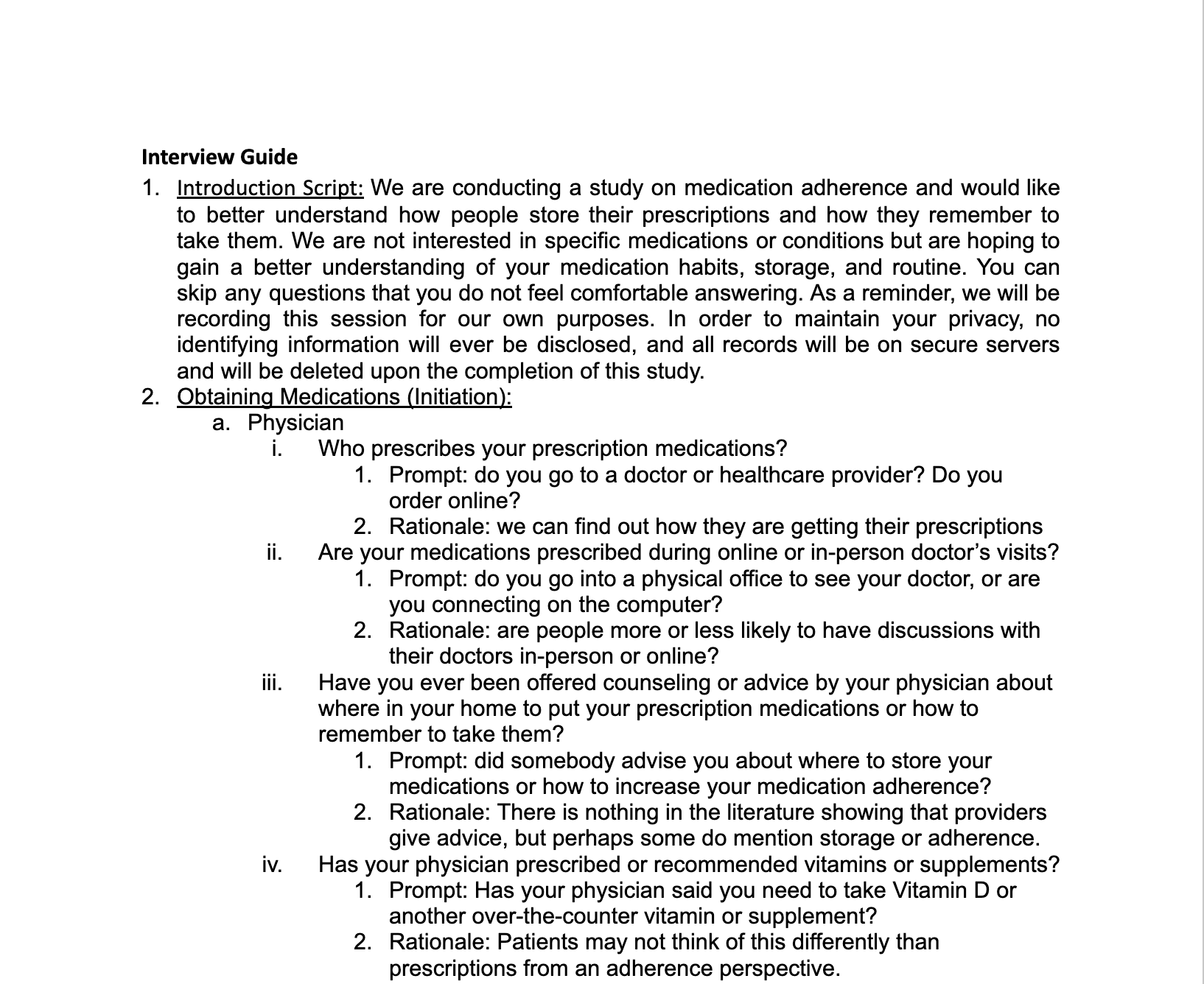

The interview guide was designed to elicit information about daily routines and perceived barriers to and facilitators of adherence. The guide started out with simple, straightforward questions to more complex ones. Interview questions were designed to cover the three components to adherence —initiation, implementation, persistence— to fully address the stages of adherence. Below are some themes we addressed in each component of adherence:

"I came up with a scheme, where I keep the medicines on one side of my microwave, or my toaster oven. When I take it, I put it on the other side."

– Participant 4

.png)

"If I have to go somewhere, first thing in the morning, that's a typical time when I forget. Because sometimes I don't even have time for breakfast or for one reason or another didn't get around to it. Then the next day, it's Monday, but I'm looking at the Sunday case saying, ‘Oh, I guess I forgot to take it yesterday.’ " –Participant 7

This was my first time working in a research setting. While I have done interviews in the past for design projects, this was my first time working on an interview study that was irb approved. I learned how to present our findings with scientific integrity and accuracy, learning to be critical of the strengths and weaknesses in our study and being rigorous about my writing.

The questions asked provided an in-depth look at home medication management through the participants’ experiences. Face to face interviews through Zoom enabled us to gain more insight and details that we didn't discover through our precious survey study.

Our sample size of 22 participants is too small to draw universal conclusions. In addition, with an average age of 70 years old, many participants were not working full-time. Thus, their daily routines, mainly living stationary in their homes, are different to those of young adults or teenagers and results cannot be extrapolated to those ages.

Lastly, participants were limited to those taking 1-3 medications and experiencing no cognitive decline. As participants were recruited through OSHER, most were highly educated, which is associated with higher health literacy and socioeconomic status. A more representative sample of older adults would need to include those with numerous medications with complicated schedules, those who are experiencing varying levels of decline, and those with different levels of education, which would add additional barriers to adherence.

A bigger and more diverse sample in terms of socioeconomic status will allow us to understand the different barriers people face in terms of home medication management.

If we were to conduct another interview, we would want to separate participants into two groups: those who use pill cases and those who use the prescription bottle. This would allow us to ask more specific questions to each group, and we would likely learn more about differences in routine and storage, and their effect on adherence.

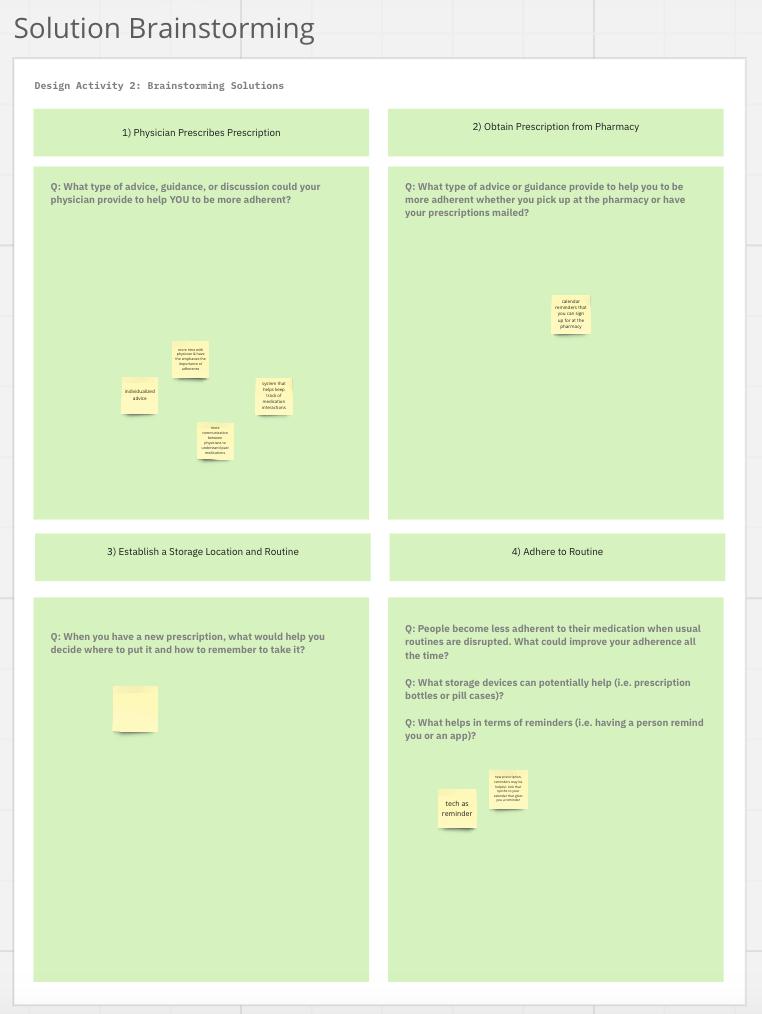

Based on our study, we learned that patients develop their adherence strategy through trial and error and do not receive help from healthcare professions. What are touchpoints in the healthcare system where interventions can happen and what would effective interventions look like?

Current medication adherence devices rely on time-based reminders. As we found in our study, most people think of their medication in the context of a routine and do not take medications at an exact time. Current devices provide constant alerts and reminders, resulting in alarm fatigue. Thus, we should consider a new medication adherence device that uses context aware reminders, reminding users only when they forget.

This was my first time working in a research setting. While I have done interviews in the past for design projects, this was my first time working on an interview study that was irb approved. I learned how to present our findings with scientific integrity and accuracy, learning to be critical of the strengths and weaknesses in our study and being rigorous about my writing.

The questions asked provided an in-depth look at home medication management through the participants’ experiences. Face to face interviews through Zoom enabled us to gain more insight and details that we didn't discover through our precious survey study.

Our sample size of 22 participants is too small to draw universal conclusions. In addition, with an average age of 70 years old, many participants were not working full-time. Thus, their daily routines, mainly living stationary in their homes, are different to those of young adults or teenagers and results cannot be extrapolated to those ages.

Lastly, participants were limited to those taking 1-3 medications and experiencing no cognitive decline. As participants were recruited through OSHER, most were highly educated, which is associated with higher health literacy and socioeconomic status. A more representative sample of older adults would need to include those with numerous medications with complicated schedules, those who are experiencing varying levels of decline, and those with different levels of education, which would add additional barriers to adherence.

A bigger and more diverse sample in terms of socioeconomic status will allow us to understand the different barriers people face in terms of home medication management.

If we were to conduct another interview, we would want to separate participants into two groups: those who use pill cases and those who use the prescription bottle. This would allow us to ask more specific questions to each group, and we would likely learn more about differences in routine and storage, and their effect on adherence.

Based on our study, we learned that patients develop their adherence strategy through trial and error and do not receive help from healthcare professions. What are touchpoints in the healthcare system where interventions can happen and what would effective interventions look like?

Current medication adherence devices rely on time-based reminders. As we found in our study, most people think of their medication in the context of a routine and do not take medications at an exact time. Current devices provide constant alerts and reminders, resulting in alarm fatigue. Thus, we should consider a new medication adherence device that uses context aware reminders, reminding users only when they forget.