How can we make medication management, a crucial component to aging well, easier for older adults? Adhering to medication is a difficult task for older adults and few products are clinically shown to effectively improve adherence. Furthermore, it is estimated that 50% or more of U.S. adults do not take their prescriptions as directed, and that medication non-adherence is responsible for as many as 33%-69% of hospital admissions and 125,000 deaths annually.

As researchers, we are interested in understanding the barriers older adults face when trying to take prescriptions as prescribed and what solutions can improve at-home medication adherence. After conducting a survey and interview study to understand adherence routines, we wanted to directly hear from older adults about what would help them develop successful adherence routines. However, current medication adherence solutions are generally designed for, instead of with, intended patient populations.

How can we make medication management, a crucial component to aging well, easier for older adults? Adhering to medication is a difficult task for older adults and few products are clinically shown to effectively improve adherence. Furthermore, it is estimated that 50% or more of U.S. adults do not take their prescriptions as directed, and that medication non-adherence is responsible for as many as 33%-69% of hospital admissions and 125,000 deaths annually.

As researchers, we are interested in understanding the barriers older adults face when trying to take prescriptions as prescribed and what solutions can improve at-home medication adherence. After conducting a survey and interview study to understand adherence routines, we wanted to directly hear from older adults about what would help them develop successful adherence routines. However, current medication adherence solutions are generally designed for, instead of with, intended patient populations.

Co-design is a way of directly involving intended users in the ideation process. Unlike traditional design practices where practitioners design for people, co-design emphasizes designing with people. Hosting a co-design workshop, where we could collaborate with people directly and hear their voices and desired solutions, seemed like the perfect strategy to meet our research objective.

We hosted a pilot workshop with one participant to testrun our agenda, specifically to check if our questions were worded clearly and that the session length was adequate for the planned discussion. As an adjustment for the actual workshop, we decided to incorporate an online whiteboard, Miro, to guide and record the discussion.

We recruited our participants through two posts in a newsletter with a signup link to the members of OSHER Lifelong Learning Institute at Tufts University, whose members are over the age of 50. While more signed up, our co-design workshop took place online with three participants.

Workshop took place on Zoom for 2 hours.The workshop was organized around identifying problems and brainstorming designs around four phases of taking prescription medications:

Our workshop consisted of group design activities and discussions for each of these four phases.

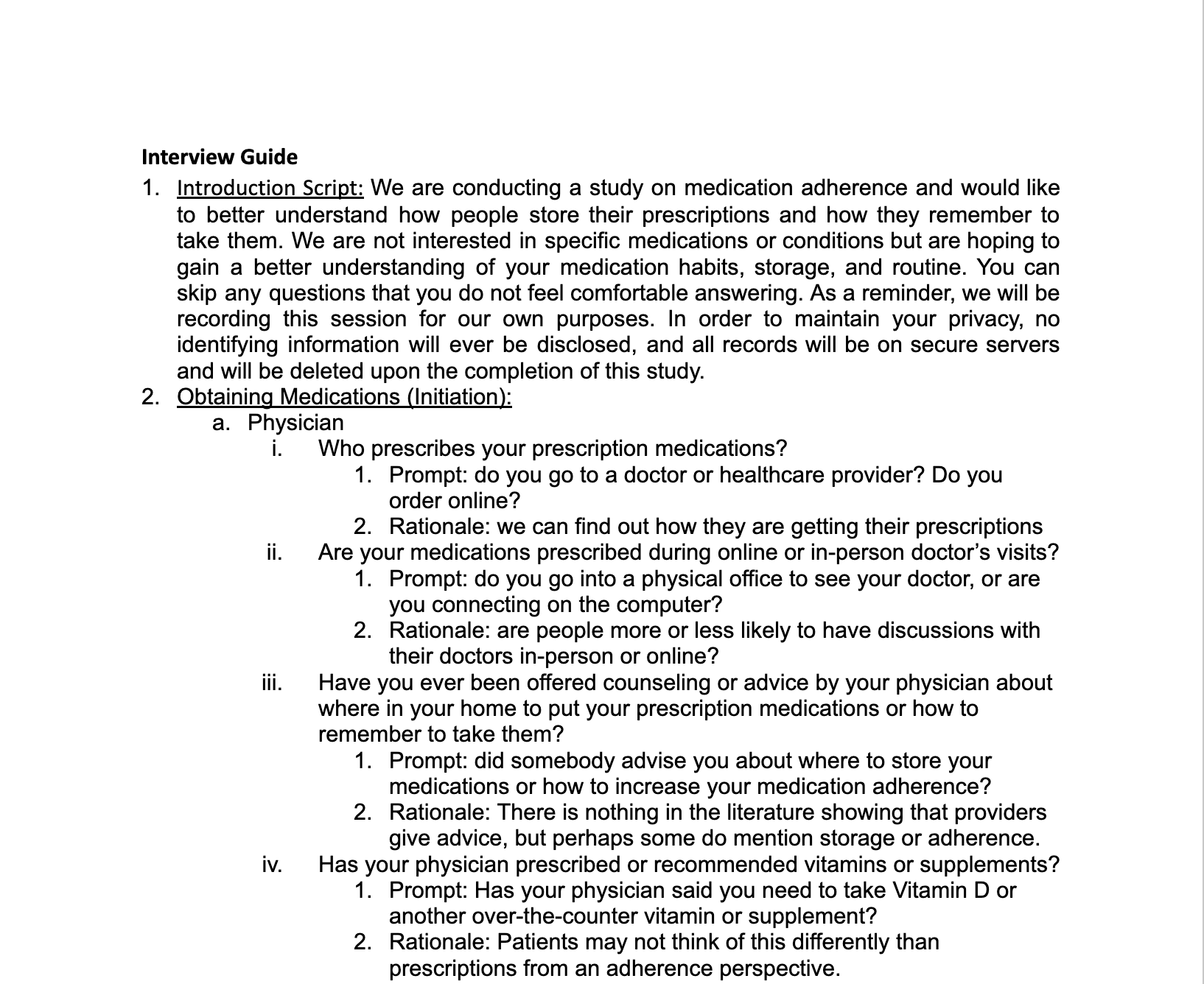

The interview guide was designed to elicit information about daily routines and perceived barriers to and facilitators of adherence. The guide started out with simple, straightforward questions to more complex ones. Interview questions were designed to cover the three components to adherence —initiation, implementation, persistence— to fully address the stages of adherence. Below are some themes we addressed in each component of adherence:

"I came up with a scheme, where I keep the medicines on one side of my microwave, or my toaster oven. When I take it, I put it on the other side."

– Participant 4

.png)

"If I have to go somewhere, first thing in the morning, that's a typical time when I forget. Because sometimes I don't even have time for breakfast or for one reason or another didn't get around to it. Then the next day, it's Monday, but I'm looking at the Sunday case saying, ‘Oh, I guess I forgot to take it yesterday.’ " –Participant 7

In our workshop, participants identified 3 major problems surrounding medication adherence.

Adherence cannot be improved without addressing the larger problems of depersonalized and fragmented care in the healthcare system. There was a general frustration and feeling of disempowerment in each phase of the process of prescribing, obtaining, taking, and refilling prescription medications.

Participants expressed that physicians were not in clear communication with each other about what medications were being prescribed to them and possible conflicts. One participant shared an incident of a friend who had medication prescribed by different doctors to treat the side effects of a previous drug, which led him to take numerous drugs due to this “layered” effect. The lack of communication between physicians made it difficult to completely trust a physician’s prescription.

Participants felt that when a physician prescribed them medication, it was not much of a conversation as it was a list of reasons for taking the medication, what the medication was, and how to take the medication. Physician advice was always very generic rather than individualized. Participants also felt that they did not have enough time with the physician to have all their questions fully answered.

At the pharmacy, when given the option to speak to a pharmacist by the technician, participants said that they sometimes opted out due fear of holding up a long line. There was also often a lack of privacy when talking to a pharmacist in public.

Participants expressed that they would much rather receive advice from their physician, who they have built a long-term relationship with, than their pharmacist, who is a different person at each visit.

Participants revealed that they always do an online search to confirm or enhance advice received from their physicians or pharmacists.

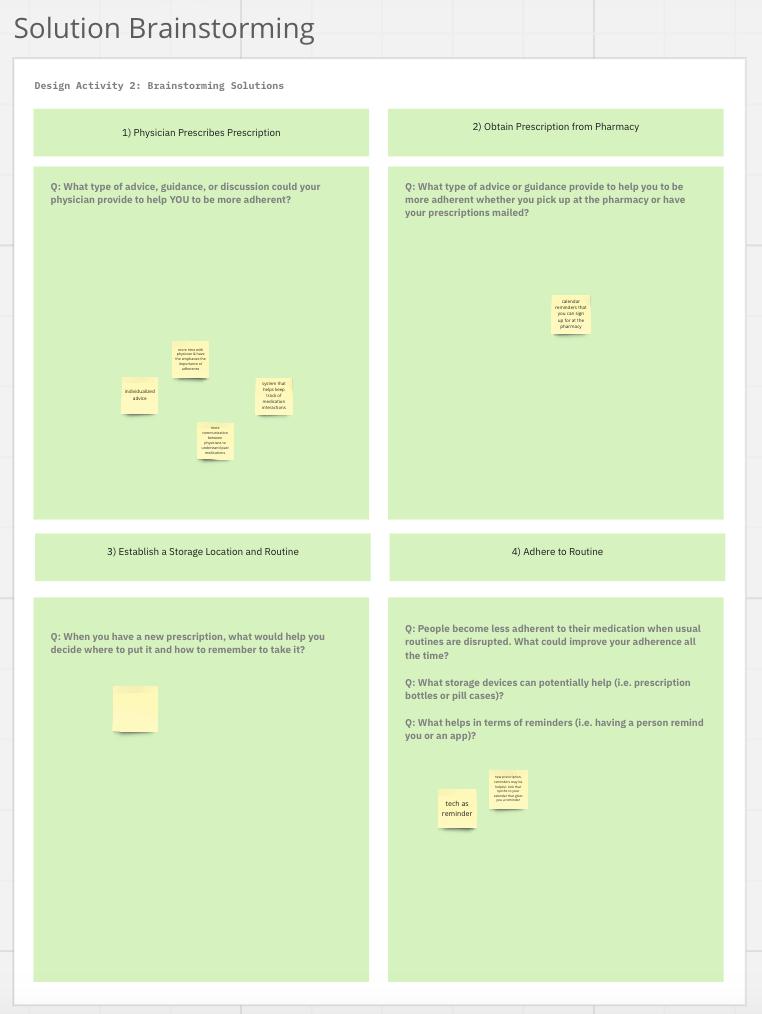

After identifying key problems, participants brainstormed design solutions.

Although all recruited participants did not have any trouble adhering to their medication, they identified understanding why they are taking their medication and its importance is crucial to being adherent. Participants suggested that having a doctor who knows them well to explain the gravity of adhering to medication may improve adherence outcomes.

Inspired by refill text reminders, another idea was to have an opt-in for calendar reminders at the pharmacy.

People have a desire to build stronger relationships with their physicians and would be more susceptible to advice if they feel the advice giver knew them well. They want more time with their physicians to have questions fully answered and desire more personalized guidance about taking a new medication.

Since all participants did not struggle with adherence, they strongly felt that adherence was a personal responsibility and that more advice from physicians, pharmacists, or assistance from technology would not be helpful to them currently. Thus, participants had some difficulty in brainstorming solutions. Catering to this demographic, a better framing to pivot to for the workshop would have been “How can you use your experiences and success with adherence to design for others?” We can improve the workshop’s structure by presenting a “design brief,” providing more context about why people struggle with adherence.

We want to revise our recruitment strategy to target people who struggle with adherence. While discussing design solutions with individuals who are adherent gives us a special viewpoint from those who already know what makes a successful medication management strategy, they lacked perspective about why others were not adherent. By directly involving people who struggle with adherence, we can gain valuable insight into this perspective.

Following the spirit of co-design, there is huge potential in physically going to the communities we are designing for and bringing our workshop to them. We are currently planning an in person workshop with Brookhaven, a senior living community in Lexington, MA. Other future workshop locations would be nursing homes, senior centers, and assisted living facilities.

People have a desire to build stronger relationships with their physicians and would be more susceptible to advice if they feel the advice giver knew them well. They want more time with their physicians to have questions fully answered and desire more personalized guidance about taking a new medication.

Since all participants did not struggle with adherence, they strongly felt that adherence was a personal responsibility and that more advice from physicians, pharmacists, or assistance from technology would not be helpful to them currently. Thus, participants had some difficulty in brainstorming solutions. Catering to this demographic, a better framing to pivot to for the workshop would have been “How can you use your experiences and success with adherence to design for others?” We can improve the workshop’s structure by presenting a “design brief,” providing more context about why people struggle with adherence.

We want to revise our recruitment strategy to target people who struggle with adherence. While discussing design solutions with individuals who are adherent gives us a special viewpoint from those who already know what makes a successful medication management strategy, they lacked perspective about why others were not adherent. By directly involving people who struggle with adherence, we can gain valuable insight into this perspective.

Following the spirit of co-design, there is huge potential in physically going to the communities we are designing for and bringing our workshop to them. We are currently planning an in person workshop with Brookhaven, a senior living community in Lexington, MA. Other future workshop locations would be nursing homes, senior centers, and assisted living facilities.